| The Roots of Quebec Separatism

The Canada eZine - Quebec

By Charles Moffat - November 2007. Before I go into great detail regarding the issue of the causes of the Quebec Separatist movement let us first look at the history and demographics instead. A Brief History of Separatism: Beginning in the 1960s Quebec was the center of terrorist movement attempting to separate Quebec from the rest of Canada and establish a French-speaking nation. As a result in 1969 French and English were both declared the official languages of Canada, where previously the whole Canada had one official language: English. In 1970 a series of terrorist attacks by separatists ended with the kidnapping and murder of Quebec's minister of labor and immigration, Pierre Laporte. The federal government sent in troops and temporarily suspended civil liberties. In 1974 French became the official language of the province of Quebec. In the 1976 provincial election a party sympathetic to separatism won the election and passed several measures to strengthen the movement. Under a controversial law adopted in 1977, education in English-language schools was greatly restricted. The charter also changed English names of towns and imposed French names as the language of business, court judgments, laws, government regulations, and public institutions. A referendum in 1980 to become an independent country was overwhelmingly rejected by the Quebec voters. The Quebec provincial government opposed the 1982 constitution, which included a provision for freedom of language in education, and unsuccessfully sought a veto over constitutional change. In 1984 the Supreme Court of Canada ruled against Quebec's schooling restrictions and declared that English and other minority languages must be taught in schools where those languages are more dominant (ie. Italian in Montreal or Native languages in Native communities). In 1987 the Meech Lake constitutional accord recognized Quebec as a "distinct society" and transferred extensive new powers to all of the provinces included Quebec. The provincial government of Quebec promised that it would accept the 1982 constitution if the accord was approved by all the rest of the provinces. The House of Commons ratified the Meech Lake accord on June 22, 1988, but the accord died on June 23, 1990, after Newfoundland and Manitoba withheld their support. A new set of constitutional proposals hammered out by a parliamentary committee was agreed upon in 1992. They called for decentralization of federal powers, an elected Senate, and special recognition of Quebec as a distinct society. In a referendum held in October 1992, Canadians decisively turned down the constitutional changes. In the 1995 referendum to separate from Canada again Quebec voters declined by a narrow margin of 50.58% "No" to 49.42% "Yes". The premier of Quebec Jacques Parizeau blamed the no vote on minorities and immigrants. Since then the Separatism movement has been searching for strong leadership (including the dramatic rise and fall of Andre Boisclair) and Quebecers have started shifting their views towards voting for the Conservative Party and back to federalism, but the movement is hardly dead. It is just leaderless for the time being.

Language Statistics and Demographics: Precise statistics of what languages people speak in Quebec vary depending on what government agency or political group you are talking to. According to one source the language breakdown of mother tongues is as follows:

According to another it is

The most reliable numbers I could find is the 2001 Census by Statistics Canada which states of a total population of 7,125,580 there is:

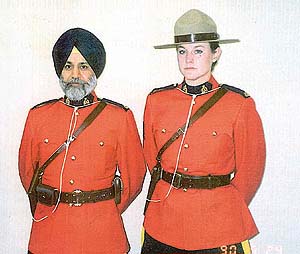

An additional 97,350 identified themselves as bilingual, including 50,060 who said they spoke both English and French which places English/French bilingualism at 7.02%. Other sources claim bilingualism is as high as 41%, but this is not true according to the 2001 Census. The Roots of Separatism: What is not mentioned in the above statistics is the amount of immigration Quebec has received over the years. The metropolitan city of Montreal for example has seen huge immigration and has become a mecca for English speakers and people who speak English or French. In the 1951 Census only 3.7% of Quebec's population spoke a different language, but the number has since risen to approx. 10%. Thus it starts to become clear why former Quebec Premier Jacques Parizeau blamed immigrants and Natives for the success of the Non vote and we get an inkling of why Separatism started in the 1960s. Between 1951 and 1976 the number of minority languages in Quebec almost doubled to 7.2%. Following World War II Quebec became a haven for NAZI war criminals who addition to speaking German also spoke French. They fled Europe and arrived in Canada speaking fluent French and hid inside Quebec, which at the time was predominantly caucasian. The exact number of NAZIs who came to Quebec is unknown, but it is quite likely they found sympathizers here in Canada. There has been decades of hatred in Quebec towards the strong Jewish population in Montreal, the waves of immigrants in the 1960s, 1970s & 1990s, and the ever growing population of non-White / non-French speakers. Today we hear about incidents of intolerance almost daily coming from Quebec. The roots of Separatism start to become abundantly clear: It is about culture and race. For years Quebec Separatists have been making their arguments that they are attempting to preserve their culture, that they are a distinct society and that they only want French speakers immigrating to Quebec, but there is a problem with that: France (and other Francophone countries) have become quite multicultural over the years and as is the case with many immigrants they speak multiple languages. Thankfully Canadian immigration laws cannot discriminate based on race, but we do keep very careful track of language (and we make exceptions for refugees), but with the rise of English as an international language means that it is becoming increasingly easier for immigrants from all over the world to come to Canada through several convenient rules in the system: A higher level of education, practicing a trade and business opportunity for entrepreneurs. The latter of these three is the biggest one because it means that any immigrant who wants to start their own business just has to pass a basic language test and they're in. One of the key features of Quebec Separatists is their desire to control their own immigration, but even if they did gain more control over their own immigration immigrants would still find a way to jump through the rules. Make it too difficult and there won't be enough skilled labourers to do all the work, because Quebec has a low birth rate. Which brings us to another issue: Low birth rates of Francophones. French speakers are not having enough children, whereas immigrants tend to have large families. The overall result is more multiculturalism in schools and a growing block of voters who were raised in Canada, proud of being Canadian and aren't so concerned about about the issues of "French Culture" in Quebec. We can't just eliminate centuries of tension between English-Quebec and French-Quebec by restricting immigration to only French speakers however, because there is another issue at stake: English-Canadians moving to Quebec. As a province of Canada any Canadian can at any time move to Quebec, travel there, start a business there, get married and have kids there. Since 1951 however its actually been the reverse. In 1951 approx. 14% of Quebecers were English-speaking and quite a few have since moved to other parts of Canada (perhaps sensing they were not welcome there). The biggest change occurred in the 1980s and 1990s, periods of political turmoil with two referendums and the Meech Lake Accord.

But while English speakers have dropped in porportion, they have still grown in overall number thanks to population growth and urbanization. Most English speakers live in metropolitan areas, as do many immigrants, and so it really comes down a conflict between rural regions of French speakers and urban regions where multiculturalism is dominant. If we compare on a map for example where people voted yes and where they voted no in the 1995 referendum we see a very clear distinction. The Native regions (mostly in Northern Quebec and along the border of Ontario) voted No because their land treaties are with the Canadian government (which makes an interesting argument as to whether Quebec can even separate from the rest of Canada because it would violate a number of land treaties). The areas surrounding Montreal (where many English speakers and immigrants live) voted No as well. Indeed it is really only the isolated and more rural regions of eastern Quebec that voted overwhelmingly Yes. We can conclude therefore that it is really matters of isolation, intolerance and ignorance that are driving the separatist movement. |

|

The Matter of Religion:

The Matter of Religion:

When the British defeated the French in the early stages of Canadian history they allowed the Quebec people to keep their language and their religion (Catholicism). And therein lies another problem. For centuries Quebec has been overwhelmingly Catholic, but the influx of non-Catholic immigrants has created political problems as the Quebec people have grown accustomed to religious discrimination, particularly against Muslims in recent years. Small surprise. Arabic is one of the fastest growing mother-tongues in Quebec. More and more highly educated and French or English speaking Muslims are coming to Quebec, largely due to huge advances in language schools in the Middle East, but also coming from France as well (which now has a huge Muslim population). The globalization of languages and religions as people spread around the globe is not suiting some people in living in rural Quebec. They would prefer everyone was white, spoke French and was Catholic. We have to remember what kind of people live in rural Quebec. Farmers, trades people and a relatively small number of people with a college or university education. Not the most liberal and forgiving sort of people. Former Quebec Premier Maurice Duplessis of the Union Nationale, a Quebecois nationalist and economic conservative, tried to keep Quebec Catholic and conservative, but the pressures to reform were too much. In the 1960s the movement to defend Quebecois culture, religion and language moved into the political arena with Liberal Premier Jean Lesage's "Quiet Revolution," which included reforms to the social and educational infrastructure, controls on corruption, nationalization of power companies, and limiting the Catholic church's influence on politics, all designed to modernize Quebec society. But when the Union Nationale returned to power in 1966 it was seen as a sign that Quebecers wanted back to control of such things and didn't want the Canadian federal government meddling with Quebec's religion and culture. From the fringes of this dispute a movement began to emerge that thought that Quebec would never be able to realize its goals within the federalist system, or within Canada, and began to push for independence from Canada. As a result, the separatist Parti Quebecois was formed led by Rene Levesque. It was also around this time, at the 1967 Worlds Fair in Montreal, that French President Charles de Gaulle, a devout Roman Catholic, closed a speech with "Vivre le Quebec libre!" ("Long live free Quebec"), drawing anger from the Canadian government and the adoration of separatists. It was then that the modern separatist movement began in earnest. Shortly afterwards the Front de Liberation Quebecois (Quebec Liberation Front, or FLQ) started its campaign of bombing political and religious targets in Quebec. Acts of Terrorism: The FLQ, inspired by Marxist ideology, sporadically planted bombs and in 1963 bombed the Montreal Stock Exchange, populated at the time mostly by English speakers or bilinguals. In 1970 they kidnapped British trade commissioner James Cross and Pierre Laporte, Quebec's Minister of Labor. The kidnappings prompted then Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau to declare martial law in Montreal and suspend some civil liberties. The terrorists killed Laporte (Cross was released unharmed) and the FLQ became known as a group of violent extremists, which resulted in an anti-separatist backlash.

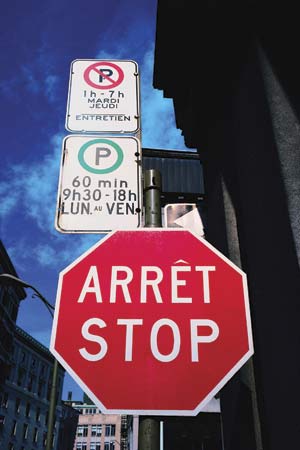

Political Changes: The Parti Quebecois became the Official Opposition to Premier Henri Bourassa's Liberal government in 1973 and finally took power in 1976. The Parti Quebecois instantly introduced measures to strengthen the use of the French language in the province, making it the official language of government and the courts, thus discriminating against any judges or lawyers who spoke English instead. They also made it the language of business (all shop signs in Quebec must have French twice as large and twice as prominent than English). Most infamous was the passage of Bill 101, which in addition to restricting English-language education, it required that all immigrants moving to Quebec enroll in French-language schools, regardless of the language they previously spoke. Finally, the Parti Quebecois called a referendum in the province on the question of separation from Canada in 1980, but it was defeated with only 40% voting in favor. Parti Quebecois Premier Rene Levesque adopted a strategy known as the "beau risque" which believed that a political solution short of separation would be possible with Canada. Quebec did not approve the 1982 Constitution which the other provinces approved and ratified with the Constitution Act of 1982. Quebec's refusal of the Constitution Act prompted the federal government to pursue what would be known as the Meech Lake Accord, designed to increase the power of the provinces and recognize Quebec as a "distinct society" within Canada. While the House of Commons ratified Meech Lake in 1987, Manitoba and Newfoundland withdrew their support in 1990, and the Accord was dead. A second attempt was made, this time referred to as the Charlottetown Accord, which included Meech Lake as well as a "Canada Clause" (providing for ethnic duality instead of bilingualism), a right to negotiate for autonomy with First Nations, and some other additions. However, this failed with 54% opposed nationwide, and only New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Ontario and the Northwest Territories approved it. At a Parti Quebecois policy convention in Montreal in 1985 a majority of delegates voted not to fight the next election on the question of sovereignty. This led to many enraged hard-line delegates walking out of the conference. Soon after, Rene Levesque resigned as Premier and leader of the Parti Quebecois. Pierre-Marc Johnson succeeded him as leader of the Parti Quebecois, but was defeated by the Liberals led by Robert Bourassa only a few months later. The Bloc Quebecois was also founded with the intention of representing Quebec's interests in Canada's Parliament, becoming a sort of Parti Quebecois on the national level. Gilles Duceppe became the first Bloc MP in the House of Commons following a 1990 by-election. The Bloc enjoyed almost instant success, becoming the Official Opposition in 1993, the same election that saw the Liberal Party and Jean Chretien come to power. One year later, the Parti Quebecois, now led by Jacques Parizeau, came to power in Quebec and promised to hold a referendum on sovereignty. The sovereignty law began to be drafted almost as soon as the Parti Quebecois came to power and three political parties, Parizeau's Parti Quebecois, the Bloc Quebecois led by Lucien Bouchard, and the Action Democratique led by Mario Dumont agreed on a final law and to hold referendum on the question. The referendum was finally held on October 30, 1995. The vote was even closer than the 1980 referendum, with 49.4% voting in favor, and 50.6% voting against. When the results of the vote were released, a visibly enraged Jacques Parizeau blamed the defeat on "the ethnic vote." He resigned as leader of the Parti Quebecois and Quebec Primier one year later and was replaced by Lucien Bouchard. Conclusions: Terrorism, racism, religious fanaticism, language discrimination and extremism. Those are the roots of the Quebec Separatist movement. Separatism is certainly more controversial than politicians would sometimes admit. Of course, they don't call it racism/etc. They call it protecting Quebec's cultural heritage. But let us stop and consider a What-If Scenario: What if the Separatists won an referendum and decided Quebec should separate?

Obviously all these issues would have to be worked out, and indeed many Quebecers would have issues with specific problems and would change their mind on the matter. I don't think it would take one referendum on the matter to settle the argument. It might take 3 or 4 to completely separate. It is not as simple as a Yes or No question. There are other complex issues that would have to be asked during the process.

And by the time those questions are answered what would the result be? There would still be Canadians living in Quebec. There would still be dwindling numbers of Catholics and growing numbers of non-Catholics thanks to the birth rates, there would still be increasing numbers of Jews, Muslims and other non-Christian religions. Most importantly, they wouldn't be able to stop the language issue. While English may be dwindling in Quebec in recent years the other languages are skyrocketing in urban centres. Sooner or later the Separatists are going to come to grips with their reality: Multiculturalism is here to stay. The issue of protecting Quebec's culture will eventually die out as Quebec becomes increasingly multicultural.

| |