| Ancient ice shelf snaps free from Canada

The Canada eZine - Arctic Climate Change

Steve Lillebuen - December 28th 2006. A giant ice shelf the size of 11,000 football fields has snapped free from Canada's Arctic, leaving a trail of icy boulders floating in its wake. The mass of ice broke clear from the coast of Ellesmere Island, about 800 kilometres south of the North Pole. Warwick Vincent of Laval University, who studies Arctic conditions, travelled to the newly formed ice island and couldn't believe what he saw. "It was extraordinary," Vincent said Thursday, adding that in 10 years of working in the region he has never seen such a dramatic loss of sea ice. "This is a piece of Canadian geography that no longer exists." The collapse was so powerful that earthquake monitors 250 kilometres away picked up tremors from it. Scientists say it is the largest event of its kind in 30 years and point their fingers at climate change as a major contributing factor. "We think this incident is consistent with global climate change," Vincent said, adding that the remaining ice shelves are 90 per cent smaller than when they were first discovered in 1906. "We aren't able to connect all of the dots . . . but unusually warm temperatures definitely played a major role." The ice shelf actually broke up 16 months ago, but no one witnessed the dramatic event. Laurie Weir, who monitors ice conditions for the Canadian Ice Service, was poring over satellite images when she noticed that the shelf had split and separated. Weir notified Luke Copland, head of the new global ice lab at the University of Ottawa, who initiated an effort to find out what happened. Using U.S. and Canadian satellite images, as well as data from seismic monitors, Copland discovered that the ice shelf collapsed in the early afternoon of Aug. 13, 2005. "These ice shelves can break up really quickly, perhaps more quickly than we thought they could do in the past," he said. "Within an hour we could see this entire ice chunk just disconnect and float away." Within days, the floating ice shelf had drifted a few kilometres offshore. It travelled west for 50 kilometres until it finally froze into the sea ice in the early winter. Derek Mueller, a polar researcher with Vincent's team, saw that Ellesmere's Ward Hunt Ice Shelf had cracked in half in 2002. He also saw that sea ice, which creates a buffer zone around ice shelves, was approaching lower and lower levels. "These ice shelves get weaker and weaker as the temperature rises," he said. "And the summer of 2005 had a combination of high temperatures and strong winds that probably blew the sea ice away, making this ice shelf much more vulnerable." The Ayles Ice Shelf, roughly 66 square kilometres in area, was one of six major ice shelves remaining in Canada's Arctic. They are packed with ancient ice that dates back over 3000 years, and scientists like Vincent treat their loss as a sign that the global climate is crossing an unprecedented threshold. "We're seeing the tragic loss of unique features of the Canadian landscape," he said. "There are microscopic organisms and entire ecosystems associated with this ice, so we're losing a part of Canada's natural richness." Meanwhile, the spring thaw may bring another concern as the warming temperatures could release the ice shelf from its Arctic grip. Prevailing winds could then send the ice island southwards, deep into the Beaufort Sea. "Over the next few years this ice island could drift into populated shipping routes," Weir said. "There's significant oil and gas development in this region as well, so we'll have to keep monitoring its location over the next few years."

Ellesmere Island, Northern CanadaThe Arctic’s largest ice shelf is breaking up. The Ward Hunt Ice Shelf is a remnant of the compacted snow and ancient sea ice that extended along the northern shores of Ellesmere Island in Northern Canada until the early twentieth century. Rising temperatures have reduced the original shelf into a number of smaller shelves, the largest of which was the Ward Hunt Ice Shelf on the northwest fringe of the island. The Ward Hunt Ice Shelf encompasses Ward Hunt Island and covers the mouth of the Disraeli Fiord. Until recently, fresh melt water formed a 43-meter deep lake on top of almost 400 meters of seawater in the fiord. Called an epishelf lake, the relatively fresh water dammed by the 3000-year-old ice shelf became the basis of a rare ecosystem. Disraeli Fiord was the largest remaining epishelf lake in the Northern Hemisphere. Between 2000 and 2002, the Ward Hunt Ice Shelf began to crack and eventually broke in two, allowing the lake behind it to drain rapidly into the Arctic Ocean. Derek Mueller and Warwick Vincent, of the Centre d’études nordiques at Université Laval in Quebec, Canada and Martin Jeffries of the Geophysical Institute at the University of Alaska Fairbanks in Fairbanks, Alaska described the event in a paper published in Geophysical Research Letters on October 18, 2003. The series of true-color Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) images captured by the Terra satellite show the later stages of the break-up of the ice shelf and changes in the Disraeli Fiord between 2001 and 2003. The first image, taken on July 22, 2001, shows the Ward Hunt Ice Shelf as it appeared in all previous images. Though the shelf had already cracked and the lake was draining, the changes were not visible in MODIS images.

In 2002, the ice shelf began to show signs of deterioration in the MODIS images. On August 7, 2002, the ice shelf appears much as it did in 2001. The next MODIS image, taken on August 16, shows that a large chunk of ice is missing from the northern side of the shelf, to the right of the island. Mueller, et al. note that RADARSAT images likewise show that a section of the shelf broke away sometime between August 6 and August 11, though they suspect that a number of small ice islands calved off the shelf rather than one large iceberg. The MODIS image taken on August 7 narrows the time window of the event even further. The 2003 images show dramatic changes in the Disraeli Fiord. On in early July, an aqua pool of melt water formed on the surface of the ice in the fiord. By July 23, 2003, the water had drained off the ice into the fiord below, leaving no visible signs that it had ever been there. But it may have weakened the ice beneath. The ponded water could have absorbed more energy from the sun, heating and weakening the ice it rested on. It is also possible that, because the epishelf lake had drained, the ice is now mostly made up of salty seawater instead of fresh water. Salt in sea ice makes it weaker than fresh-water ice. Whether from ponded water or salt contamination, by August 29, the ice in the fiord had broken up for the first time in recorded history. This and later images also distinctly show the crack running from the fiord across the shelf to the ocean.

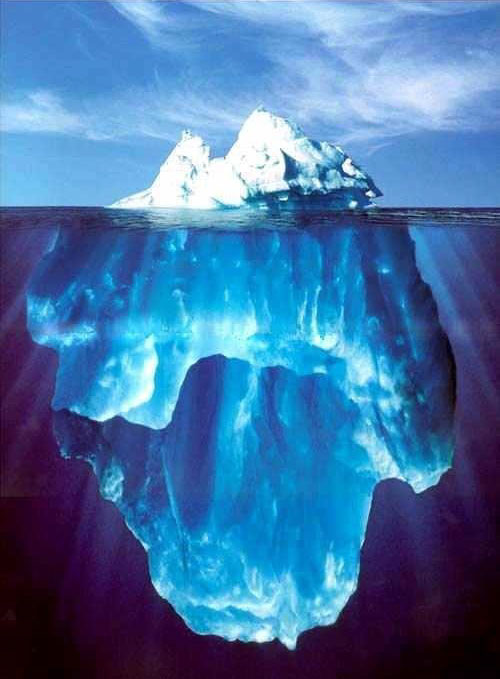

The above photograph was possible because the water was calm and the sun was almost directly overhead so that the diver [Ralph Clevenger] was able to get into the clear water and click multiple photos. The photos were then patched together using photoshop to create a singular large image of the entire iceberg. The estimated weight is 300,000,000 tons. |

|

Polar bear at threat from global warming - Bush administrationBy Andrew Buncombe - December 29th 2006. WASHINGTON - In a landmark decision, the Bush Administration has concluded that global warming is endangering the existence of the polar bear - an admission that could force the United States Government to act to curb the emission of greenhouse gases. In a sharp reversal from its previous position, the Government has decided the iconic creatures should be listed as "threatened" under the Endangered Species Act because of the widescale melting of Arctic sea ice - the bear's prime habitat. The decision by the Department of the Interior has huge implications that go beyond the survival of the polar bear; the 1973 law not only requires the Government to come up with a recovery plan for the bears but also prevents it from "enacting, funding, or authorising [actions which] adversely modify the animal's critical habitats". Campaigners said the decision provided the bear with new protection and opened the way for widespread legal action to force the Bush Administration, which has rejected the Kyoto Treaty, to limit emission of carbon dioxide and other warming gases. "I think this is a watershed decision," said Kassie Siegel of the Centre for Biological Diversity, one of three groups that petitioned the department to act. "Even the Bush Administration can no longer deny the science. This is a victory for the polar bear, and all wildlife threatened by global warming. This is the beginning of a sea change in the way this country addresses global warming." Andrew Wetzler of the Natural Resources Defence Council, added: "Global warming is the single biggest threat to polar bears' survival, and this will require the Government to address the impacts on the polar bear." It has long been known that global warming and the melting of Arctic ice were threatening the existence of polar bears, the world's largest bear whose total population is estimated at about 22,000, located in Canada, the US, Greenland, Russia and Norway. The Swiss-based Polar Bear Specialist Group of the World Conservation Union has estimated the bear's numbers will plunge by 30 per cent over the next 45 years as a result of melting ice. Anecdotal testimony from the Inuit in Alaska and Canada suggests that thinning ice and longer summers are resulting in fewer polar bears - some of which are drowning at sea, trapped on melting floes. This month researchers from the Colorado-based National Centre for Atmospheric Research suggested summer ice may disappear entirely by 2040 - 40 years earlier than previous estimates. The department said yesterday that it had decided to list the polar bear as "endangered" - a category reserved for species more likely to become extinct. The public has 90 days to comment on the decision before it is enacted. A department official told the Washington Post: "We've reviewed all the available data that leads us to believe the sea ice the polar bear depends on has been receding. Obviously, the sea ice is melting because the temperatures are warmer." Though the US is responsible for 25 per cent of the world's carbon emissions, the Bush Administration has resolutely refused to enforce limits or else enter legally binding international agreements to tackle climate change, saying such a move would damage the economy. Last month lawyers from the Environmental Protection Agency argued before the Supreme Court that the science on climate change was uncertain. They further argued that the agency was not empowered to act to curb emissions. Steadily shrinking arctic bad news for bears

Polar bears drown as ice shelf meltsWill Iredale - December 18th 2005. SCIENTISTS have for the first time found evidence that polar bears are drowning because climate change is melting the Arctic ice shelf. The researchers were startled to find bears having to swim up to 60 miles across open sea to find food. They are being forced into the long voyages because the ice floes from which they feed are melting, becoming smaller and drifting farther apart. Although polar bears are strong swimmers, they are adapted for swimming close to the shore. Their sea journeys leave them them vulnerable to exhaustion, hypothermia or being swamped by waves. According to the new research, four bear carcases were found floating in one month in a single patch of sea off the north coast of Alaska, where average summer temperatures have increased by 2-3C degrees since 1950s. The scientists believe such drownings are becoming widespread across the Arctic, an inevitable consequence of the doubling in the past 20 years of the proportion of polar bears having to swim in open seas. “Mortalities due to offshore swimming may be a relatively important and unaccounted source of natural mortality given the energetic demands placed on individual bears engaged in long-distance swimming,” says the research led by Dr Charles Monnett, marine ecologist at the American government’s Minerals Management Service. “Drowning-related deaths of polar bears may increase in the future if the observed trend of regression of pack ice continues.” The research, presented to a conference on marine mammals in San Diego, California, last week, comes amid evidence of a decline in numbers of the 22,000 polar bears that live in about 20 sites across the Arctic circle. In Hudson Bay, Canada, the site of the most southerly polar bears, a study by the US Geological Survey (USGS) and the Canadian Wildlife Service to be published next year will show the population fell 22% from 1,194 in 1987 to 935 last year. New evidence from field researchers working for the World Wildlife Fund in Yakutia, on the northeast coast of Russia, has also shown the region’s first evidence of cannibalism among bears competing for food supplies. Polar bears live on ice all year round and use it as a platform from which to hunt food and rear their young. They hunt near the edge, where the ice is thinnest, catching seals when they make holes in the ice to breath. They typically eat one seal every four or five days and a single bear can consume 100lb of blubber at one sitting. As the ice pack retreats north in the summer between June and October, the bears must travel between ice floes to continue hunting in areas such as the shallow water of the continental shelf off the Alaskan coast — one of the most food-rich areas in the Arctic. However, last summer the ice cap receded about 200 miles further north than the average of two decades ago, forcing the bears to undertake far longer voyages between floes. “We know short swims up to 15 miles are no problem, and we know that one or two may have swum up to 100 miles. But that is the extent of their ability, and if they are trying to make such a long swim and they encounter rough seas they could get into trouble,” said Steven Amstrup, a research wildlife biologist with the USGS. The new study, carried out in part of the Beaufort Sea, shows that between 1986 and 2005 just 4% of the bears spotted off the north coast of Alaska were swimming in open waters. Not a single drowning had been documented in the area. However, last September, when the ice cap had retreated a record 160 miles north of Alaska, 51 bears were spotted, of which 20% were seen in the open sea, swimming as far as 60 miles off shore. The researchers returned to the vicinity a few days later after a fierce storm and found four dead bears floating in the water. “We estimate that of the order of 40 bears may have been swimming and that many of those probably drowned as a result of rough seas caused by high winds,” said the report. In their search for food, polar bears are also having to roam further south, rummaging in the dustbins of Canadian homes. Sir Ranulph Fiennes, the explorer who has been to the North Pole seven times, said he had noticed a deterioration in the bears’ ice habitat since his first expedition in 1975. “Each year there was more water than the time before,” he said. “We used amphibious sledges for the first time in 1986.” His last expedition was in 2002, when he fell through the ice and lost some of his fingers to frostbite.

Animals scramble as climate warmsBy Patrick O'Driscoll - May 30th 2006. Alarming anecdotes — such as polar bears drowning as they swim farther in search of scarce Arctic sea ice — dramatize the issue. But a recent flurry of scientific reports, field observations and official actions suggests nature's struggle with rising temperatures is well underway: As Earth and its atmosphere grow warmer, the planet's wild inhabitants take cover where they can: cooler waters, deeper forests and canyons, higher slopes or nearer the poles, north and south. But climate scientists say if global warming continues unabated, the scramble for habitat will grow much harder for millions of species of mammals, birds, amphibians, fish, insects and more. Recent studies argue that as many as one-quarter of them could begin to disappear this century — and that warming has wiped out some already. "Nature is sending us a warning signal," says Patty Glick, a climate-change specialist at the National Wildlife Federation. "These species aren't just going extinct because they're weak. The ecosystem in which they live is changing." For as long as humans have tried to protect wild species, a key strategy has been to preserve habitat and bar encroachment by development, excessive hunting or fishing, and other threats. The USA has a 150,000-square-mile system of federal sanctuaries, with 535 refuges in all 50 states, plus 3,000 other resource sites. But rising temperatures put animals in motion, seeking new homes when they can't tolerate the old. For waterfowl, that could mean more birds in smaller spaces with less food. That can spark disease outbreaks, greater loss to predators, and cause birds to skip nesting altogether. Warming also disrupts seasonal migration, emergence from winter sleep and the foods that animals seek out then. Pollinators may not reach flowers in time. Caribou in the Arctic or marmots in the Rockies may miss plants at peak nutritional value. In Colorado, robins sometimes return two weeks earlier to areas still snow-covered, denying them access to food. Those who monitor wildlife aren't unanimous about the disruption. "The predictions are sort of all over the board on what might or could happen where," says Dale Hall, head of the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, which manages the nation's refuges. Hall says his agency has detected "minor staging shifts" in waterfowl migrations, but "subtle, not major." He says it is not yet clear if the dry-up of northern habitat is climate change or just a periodic shift in rain and temperature. Hansen of the World Wildlife Fund predicts new petitions to list more species as threatened or endangered "will be a growth activity" as the planet warms. Biodiversity A study last month in Conservation Biology builds on a 2004 paper in Nature that said one-fourth of Earth's species could be bound for extinction by 2050 if warming isn't curbed. The new report backs the earlier finding by examining 34 "biodiversity hotspots," unique areas with 44% of the world's ground vertebrate species and 35% of plant species. The study says 25 places are at significant risk. A co-author of both reports, Lee Hannah of Conservation International, calls the areas "refugee camps." Birds The National Wildlife Federation reports that at the present warming rate, several "state birds" could be flying away from those that claim them: Maryland's Baltimore oriole, Iowa and Washington's goldfinch, Georgia's brown thrasher, Massachusetts' black-capped chickadee, New Hampshire's purple finch and the California quail. Noah Matson of Defenders of Wildlife says a 2001 study by federal climate researchers predicts a 5-degree to 12-degree temperature rise by 2060 in the "prairie pothole" lands of the northern states and Canada, an essential breeding ground for waterfowl. Predicted result: Half the region's 1.3 million remote ponds dry up and there's a loss of more than half the 5 million ducks that nest there. Sea life This month, the National Marine Fisheries Service added two coral species to the USA's threatened list. Rising water temperatures and more intense hurricanes, both attributed to climate change by some scientists, are major factors in the loss of 97% of staghorn and elkhorn coral in southern Florida and the Caribbean. Climate scientist Lara Hansen of the World Wildlife Fund says coral reefs are the second-richest biological communities after rain forests. They draw vast varieties of fish — and hordes of tourists who pay to snorkel and dive among them. Due out next month: A National Wildlife Federation report on the harm that warming could do to Florida's $3.3 billion tourism business in saltwater fishing. Mammals This month, the World Conservation Union added the polar bear to its "Red List" of threatened species. In February, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service agreed to review whether to put the bear on the USA's own list after conservationists petitioned in court. In December, a University of Washington scientist reported in Journal of Biogeography that several Great Basin populations of the American pika, a small, high-altitude relative of the rabbit, have been wiped out in recent decades, in part by climate change. Amphibians A federally funded study published in January in Nature suggests global warming has wiped out dozens of species of harlequin frogs in Central and South America. The killer was a fungus that thrived because of changing temperatures. "Disease is the bullet. .. but climate change is pulling the trigger," says co-author J. Alan Pounds of the Tropical Science Center in Costa Rica. Insects Although warmer temperatures may boost pests such as bark beetles in the West and fire ants in the South, researchers are watching butterflies closely. Researchers reported in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2003 that key populations of monarch butterflies may lose their winter habitat in Mexico by mid-century to climate change there.

| |